Bugatti et les musées américains

Rembrandt Bugatti et les musées américains

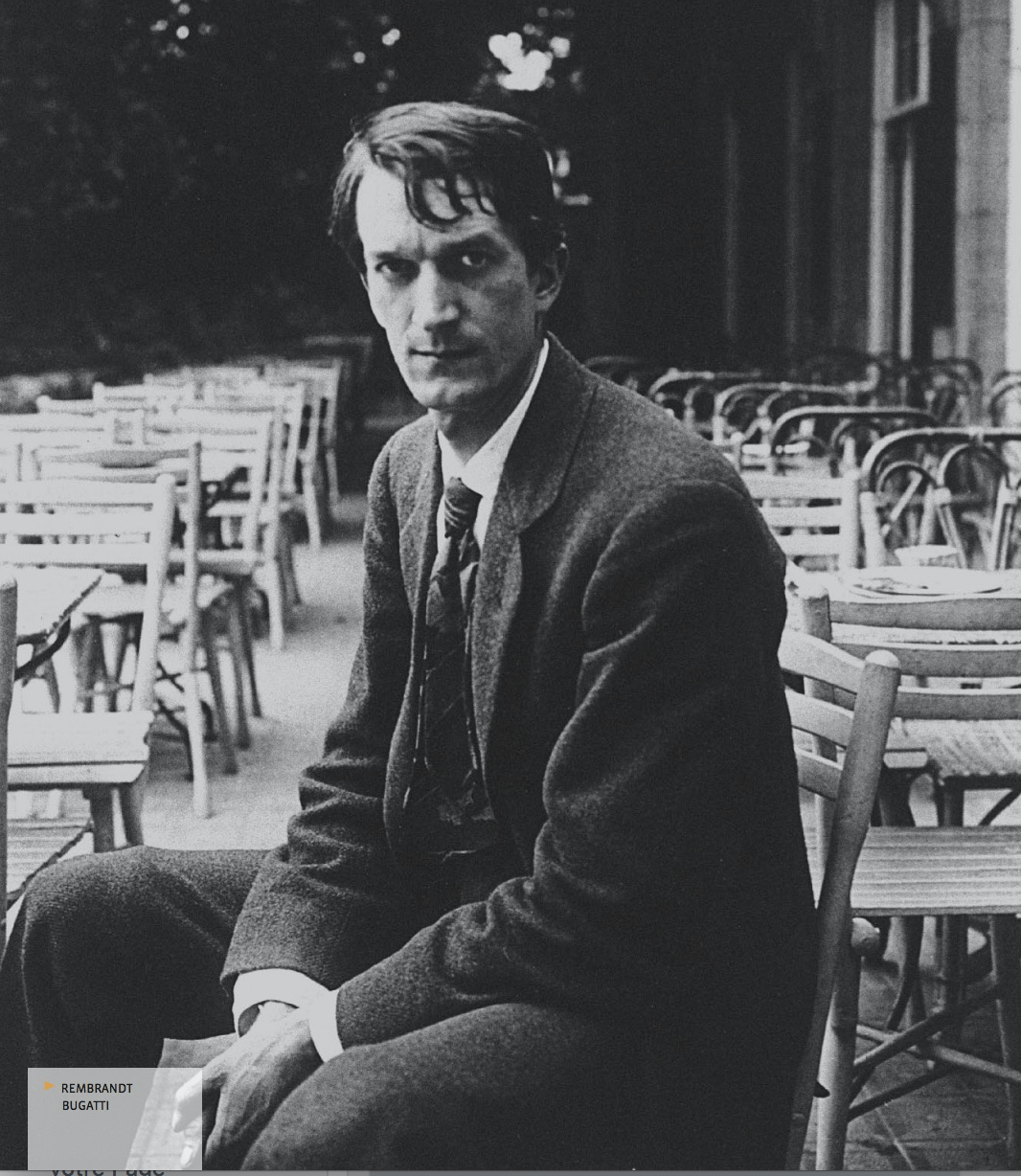

Bugatti was twenty years old when he first met Hébrard. He was a discreet, silent, solitary young man, always very carefully dressed with his own highly original sense of style.

Bugatti was an Italian from Milan endowed with a rare physical strength, an olive complexion and an abundant head of hair. When sending postcards to family or friends, his self-portrait sketches show him as half-man, half-beast, or with excessively sized arms and legs in various comical situations. At the Jardin des Plantes, his giant figure, his demeanour, his step, and his entirely natural and sophisticated elegance set him apart; a character straight out of legend or the New World.

In calling him “L’Américain”, the Muséum regulars were not so far wrong. Like Leo Tolstoy and perhaps Giovanni Segantini, Bugatti could have been a devoted reader of the American writers John Muir (1838–1914), Jack London (1876–1916), Walt Whitman (1819–1892), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) and the essayist and naturalist John Burroughs (1837–1921).

-Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, Géorgie

Zébu nain au repos (R.M.n°230), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (don de Mary et Michael Erlanger, 1994, Inv.n°GNOA1994.56)

-Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, Indiana

Girafe buvant (R.M.n°200), tirage (2), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (don de la Arthur R. Metz Foundation, 1994)

-Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

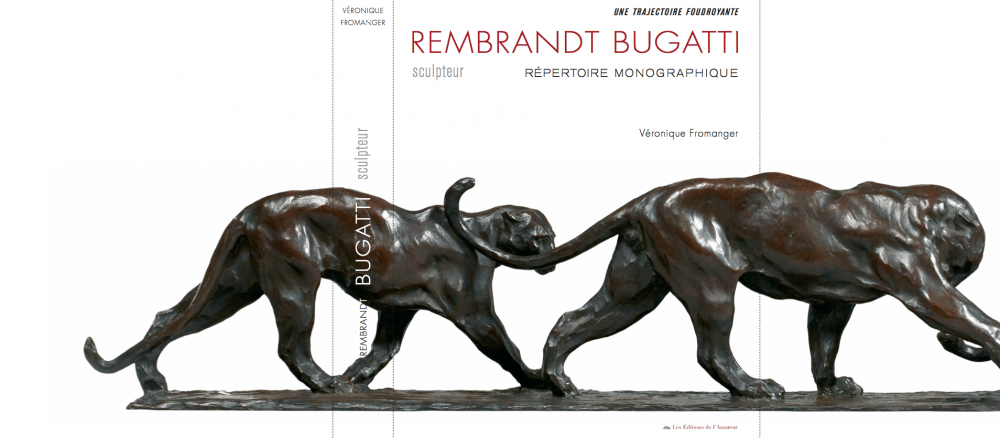

Petite Panthère marchanT (R.M.n°120), tirage (5), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (don de Mr. Noah L. Butkin, 1977)

-National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson Hole, Wyoming

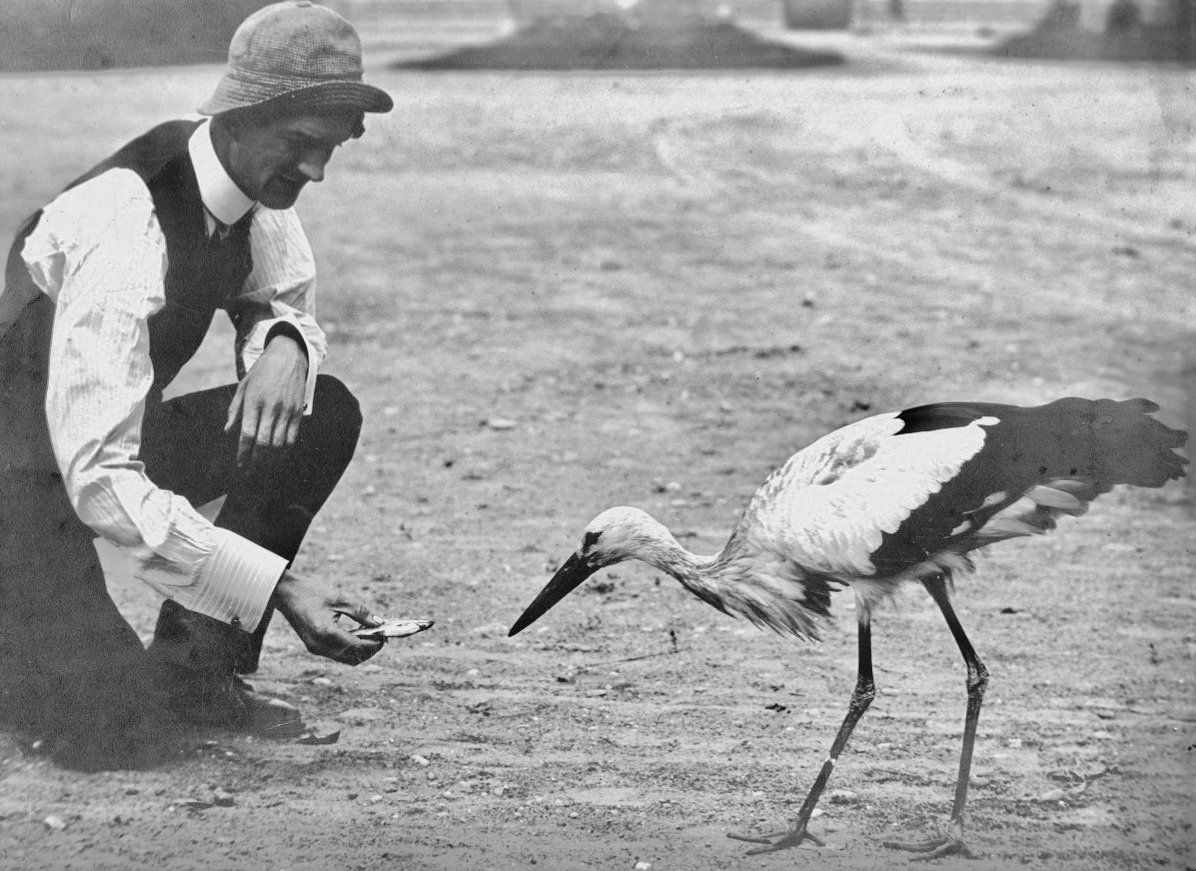

Cigogne au repos (R.M.n°188), tirage (?), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (acquisition, 2010)

Antilope « canna » (R.M.n°244), tirage (5), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (acquisition, 1998, JKMCollection JL1998.034)

Petites Antilopes goudou « deux amis » (R.M.n°272), tirage (?), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (acquisition, 2010)

-Los Angeles County Museum of Art (L.A.C.M.A.), Los Angeles, Californie

Petites Antilopes goudou (Inv.n°.31.12.31)

Autruche tête basse (Inv.n°.39.12.28) [don de Paul Rodman Mabury]

-The Mullin Automotive Museum, Oxnard, Californie

Barbara Bugatti en robe à longues manches (R.M.n°210), tirage (1), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

Jaguar assis, petit modèle (R.M.n°219), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

Jaguar accroupi, petit modèle (R.M.n°220), tirage (16), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

-The San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, Californie

Panthère marchant, patte arrière levée (R.M.n°122), Inv.n° 1938.155.a, don de Carlotta Mabury

Petit Faon axis (R.M.n°267), Inv.n° 1938.155.b, don de Carlotta Mabury, 1938

-The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, Californie

Babouin sacré « hamadryas » ou Singe cynocéphale (R.M.n°238), tirage (4), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard (don de Helen Irwin Fagan, 1975, Inv.n°1975.514)

-Hirschhorn Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. (modèles donnés par Mrs. David K.E. Bruce, 1977)

Bison d’Europe (R.M.n°26), tirage (4), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

Babouin sacré « hamadryas » ou Singe cynocéphale (R.M.n°238), tirage (9), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

Rhinocéros de trois ans (R.M.n°249), tirage (3), édition originale A.-A. Hébrard

Tigre royal (R.M.n°316), tirage (8), édition originale A.-A.Hébrard

Rembrandt Bugatti:

“I hope and indeed believe I am successful in creating a body of work like no other animalier sculptor before or since [...]”.

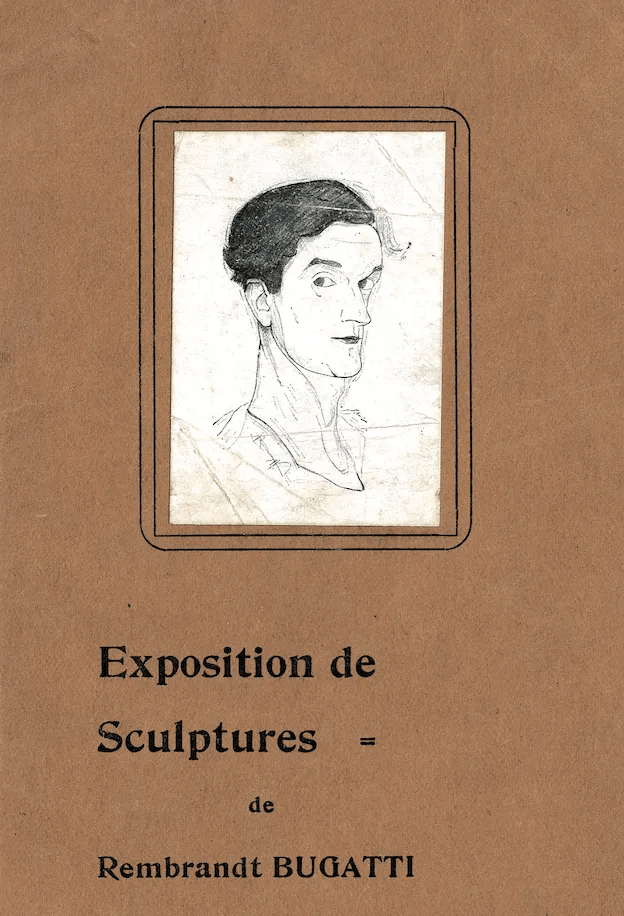

A portrait of Rembrandt Bugatti by Marcel Horteloup

Right from his earliest works, Bugatti chose the medium of modelling to express his vision of the living world. This approach would not be altered over the entire course of his brief and dazzling career. Despite his voluntary isolation and the burdens of solitude and penury he would bear, for fifteen years he had one sole obsession: to pursue his oeuvre and achieve his aesthetic ideal by “approaching perfection in his art”.

The article written by his friend the English art critic, Marcel Horteloup, in the magazine The Studio in 1906 is fundamental to understanding Rembrandt Bugatti: “You have to have seen Bugatti in his studio surrounded by his faithful companions to understand not only the joy which he got from the relationships with those he called his friends, but also the emotional attachment and admiring curiosity in his eyes when he observed the silent conversation of this little community living together [...] Bugatti will tell you, further, without boastfulness or vanity, simply stating the fact, that he knows nothing of animal anatomy, and relies solely on his eye to remain faithful to the truth. His fingers and a few centimetres of iron wire twisted into racket-shape are his only working tools, as anyone may see by watching the artist at work with his models in the Jardin des Plantes, whither he goes every morning, taking with him his supply of “plastidine.” With such enthusiasm does he praise the malleability and infinite suppleness of this wax, the only type with which, according to him, he can express himself completely, because only this wax can adapt to the different demands of the sculptor, obliged to formulate in a single material the infinitely variable components of all that he must translate. We know with which light effects, by which lighting the artist manages to create the illusion by cleverly distributing the brightness and shadow. Bugatti told me one day how the study of these questions, fundamental if he is hope to approach perfection in his art, interests him and he underlined particularly the admirable resources of the wax in which one trails a single finger in one direction or another, without altering the established plains, he manages to create tonalities, creating effects diverse enough to establish a just relationship between the differences which characterise the infinite variety of material of all things".