fromanger@rembrandtbugatti.info

Rembrandt Bugatti , Berlin 2014,Rétrospective

I precisely remember my first encounter with Rembrandt Bugatti. It was at the art exhibition in Maastricht where I suddenly landed in front of the bronze sculpture of a baboon that utterly took my breath away. I had never seen anything like it. What forms, what conception, what energy, yes, nearly aggressiveness, one could say! The shape was uncompromisingly rhythmic and geometric, its raw energy surged, so to speak, up to the surface: a lurking primate made out of cubes of completely sharp-edged floes, which appeared less like fur than like the network of naked muscles. A figure without any temporality. Was I in the 19th Century? Or in the 20th? Or in the 21st?

Of course, I knew the name of the sculptor which was written on the identification plate on that work displayed in Maastricht; I had seen pictures, of course, in the one or other monographic repertoires of his works. But never before did I have one of his works stumble directly upon me.

Today, I know that I was in luck to come across Rembrandt Bugatti in one of his major works, the hamadryas baboon, one of the most incredible sculptures that exists. For me, it was love at first sight.

Not too many years later – in the meantime, I had gone from the official advisor of the German Kulturstiftung der Länder (German Cultural Foundation of the Federal States) to the director of the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery) in Berlin – this love should find its utmost fulfilment, when, as to the question of the subject of my first own exhibition, there could only be one possible answer: Rembrandt Bugatti.

On the evening of 27th March 2014, we opened the first major solo exhibition of this artist at a museum, worldwide, who sank into oblivion after his early death, and, in spite of an international collector community, had nearly been completely ignored by museums. And, this Spring evening on the Museum Island in Berlin was, without a doubt, one of the happiest and one of the most fulfilling days in my professional life.

Delicate, dark stands with over 80 of Bugatti’s bronze sculptures spread through all of the halls of the Alte Nationalgalerie and appeared in such a way before the magnificent paintings on the walls – from Menzel and Manet, Liebermann and Böcklin, Courbet and Corot, Renoir and Segantini, Rembrandt’s Uncle, whose painting Berlin owns the magnum opus - returning home.

The sculptor Bugatti stood comparison to all of these great artists, for he was a man, who came from the 19th Century, advanced far into the 20th Century and finally created an oeuvre that left behind historic categories.

Thus, many of his sculptures appear to us today as if they were created some 20, 30 or 40 years later – a comparison with Giacometti or Marini comes to mind. And yet, there still is the immediate curiosity of the Belle Époque, which was still unbowed up to the inferno of the Great War, after which human kind was no longer the same.

And, when looking and listening carefully, it became forthwith obvious that Bugatti’s works more than merely bore comparison with the major works surrounding his in the Alte Nationalgalerie. Rather, the language of his animals suddenly elicited, from the works of the greatest masters, answers, facets, tones, which until then had been unheard.

Didn’t one hear, when observing face to face such delicate, nearly staggering panthers, the verses of Rilke’s famous poem „The Panther“, which had only come into being shortly before then at the same zoo in which Rembrandt, as well, found his models? „His gaze going past those bars / has got so misted with tiredness, it can take in nothing more. / He feels as though a thousand bars existed, / and no more world beyond them than before. “

Didn’t one believe to smell the wet earth, out of which Bugatti‘s stupendous, early cows in the Barbizon Hall of the Alte Nationalgalerie practically rose, and didn’t one become aware of this aroma from the damp forests, meadows and gardens on the paintings of Daubigny, Rousseau and Diaz de la Pena, as well?

And didn’t Manet’s magnificent in the conservatory suddenly seem that much more heated up and nebulous in the presence of Bugatti‘s potent hamadryas baboon in the hall? Didn’t the unrelated, buttoned-up human couple in that oppulent greenhouse appear that much more unsettling in the face of the two jackals, which were affectionately sniffing each other? Wasn’t it a coincidence that this painting had caused a scandal, when, in 1896, it was acquired as the first Manet, worldwide, by a museum, Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie? And, weren’t the portraits by Anton Graff that were concentrated and celebrating pure humanity suddenly an obvious frame for Bugatti‘s no less familiar portrait of the French bulldog?

Didn’t the yawning hippopotamus, which zoologists think is rather threatening, shout, as it were, a most earthly commentary across towards Böcklin’s all too meaningful isle of the dead? And, finally, didn’t the existential paintings by Max Beckmann and Lovis Corinth on the eve of World War I seem that much more relentless in view of the exciting devouring lion by Rembrandt Bugatti?

The finale to the exhibition culminated in the famous Caspar David Friedrich Hall of the Alte Nationalgalerie, quasi the heart of the German psyche, where the paintings of the great Romanticist and Bugatti’s last creations, before his suicide, formed a symbiotic relationship, which one, upon first consideration, would have thought to be, of course, less probable, for animals did not play a role in Friedrich‘s pantheistic landscapes – with one exception: the birds – the angels of heaven and death, so to speak, the intermediaries between the worlds and spheres. Thus, Bugatti’s fateful, volumetric two vultures seemed to have escaped from Friedrich‘s giant mountains, as the only creatures, who were granted to associate between the earthly and the godly – that realm, which remains inaccessible for the human imagination, according to Friedrich’s firm conviction.

And, in front of the wall in that hall, which otherwise displays the world-famous pair of paintings – the monk by the sea and the abbey in the oakwood, Bugatti’s Christ on the cross and his five old horses constituted the last image of the exhibition. Never, in the year of the commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of the beginning of World War I, did I witness human beings standing more still and, simultaneously, more moved in front of a sculpture than before Bugatti‘s five old horses; without any doubt, one of the most impressive – and still, being entirely unmelodramatic – creations in the history of art. A visitor wrote me a letter in which she told me that tears had come into her eyes.

I thought – that’s not a coincidence. Because, in the end, it wasn’t the grandiose name, the unbelievable talent or the famous family, neither the tragic story nor the Noah’s Ark of his animals, but rather the deeply perceived humanity of Rembrandt Bugatti‘s art, which connected him to Caspar David Friedrich’s incomparable landscapes and which was and still is able to touch the people at their very core.

A hundred years ago, where war and dissolution were looming on the horizon, human beings appeared barbarian to Bugatti; and animals, civilised.

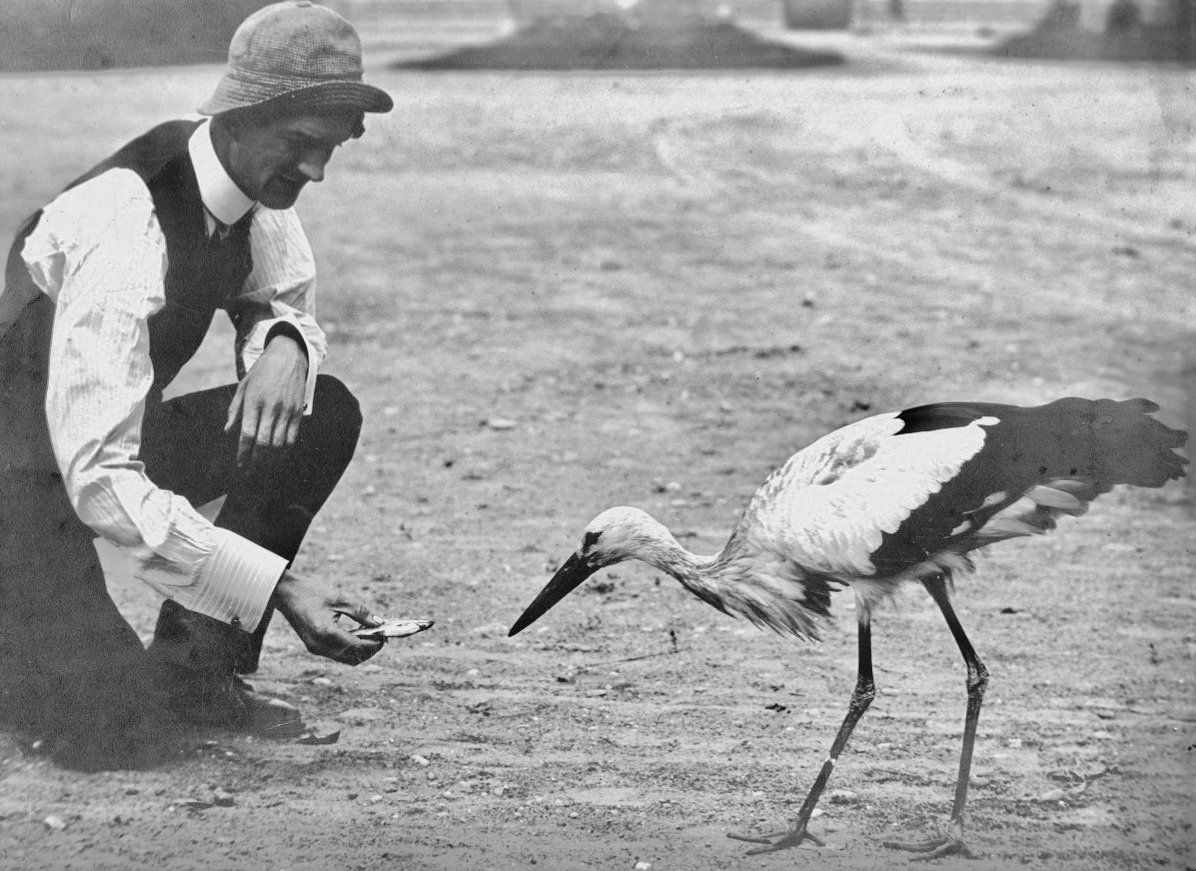

Rembrandt felt amongst humans like being in the „wilderness amongst savages“ towards the end of his life. „The work at the zoo, where I spend my days, is my only consolation”. His life was a meteorite of art history, curiously diffuse, without any tail and impact, which passed by and was soon forgotten. So, how does the world look 100 years later? Here, I make no reply. Just one thing: Rembrandt Bugatti’s art is as contemporary as ever.

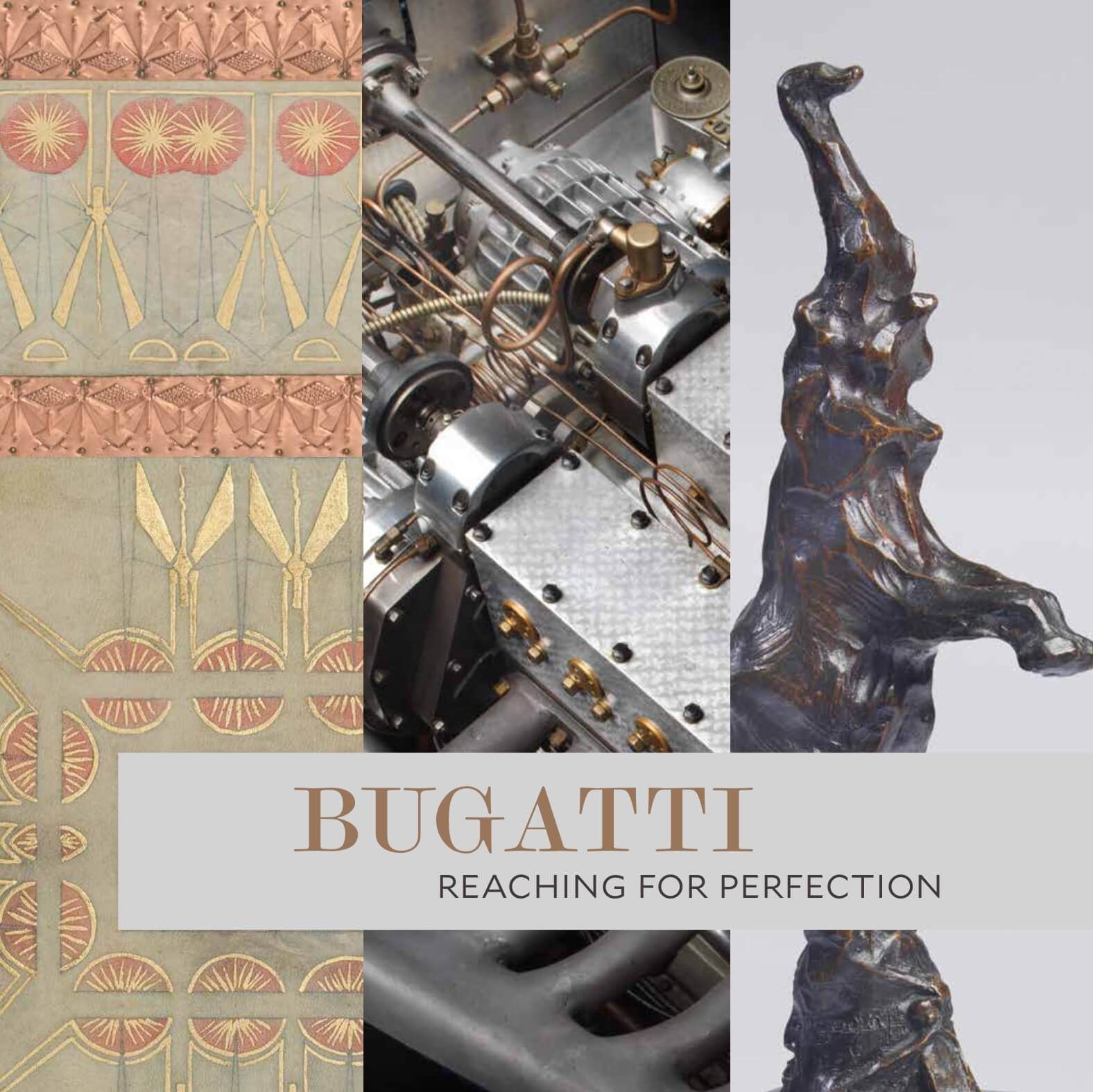

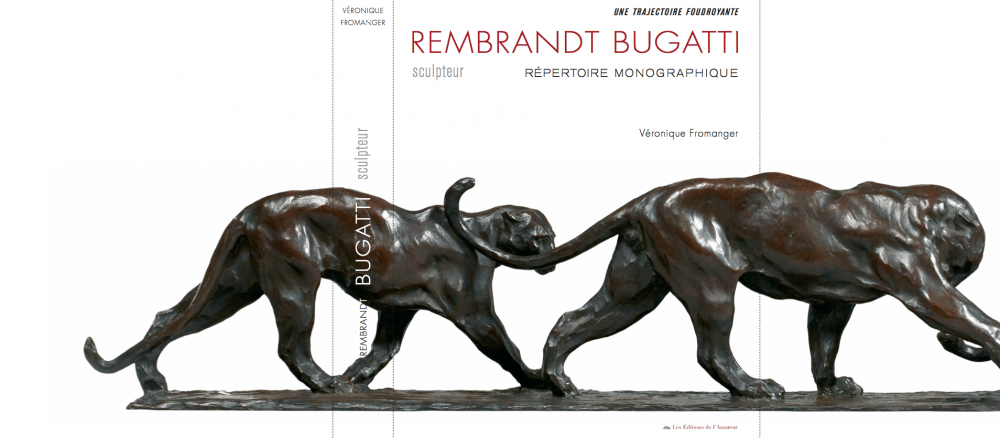

The present monographic repertoire shows us the opulence of shapes, areas and perspectives of Rembrandt Bugatti’s art, conceived with a kind of certainty and freedom that even the greatest challenges, in view of his mooching-around models, mastered without an effort: a photographic memory, a quasi one-to-one transfer from eye to hand; not an animal sculptor, rather a born sculptor per se; an absolute talent in sculpture, a man, whom every vehicle seemed to be fitting, in order to capture life in all of its forms and feelings; a portraitist of humans and animals, for whom the fauna from every continent, in the end, opened a world of patterns and structures, rhythms and means of behaviour, which, in order to tap the fullest potential, would have brought other talent to their limits.

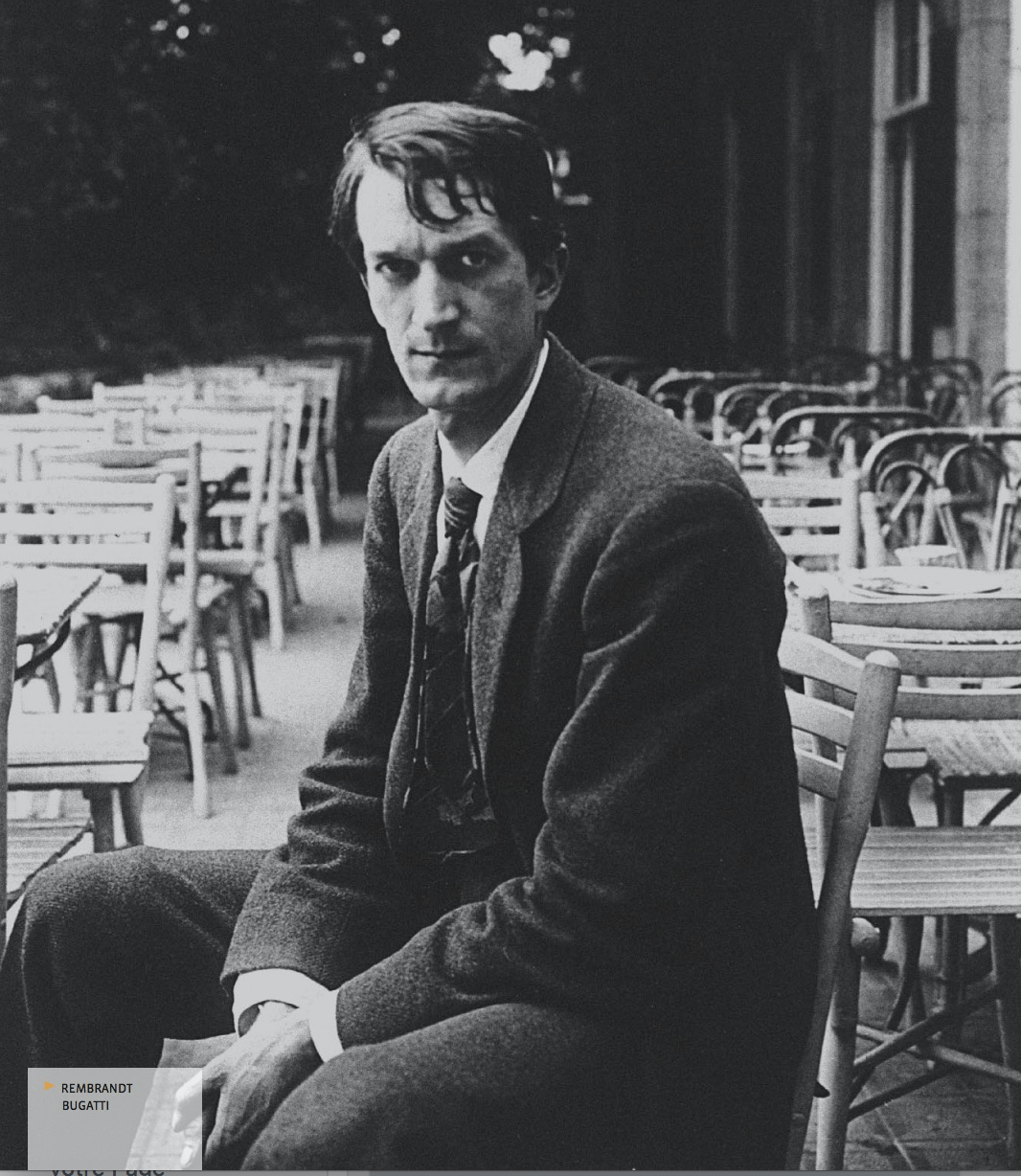

And, the monographic repertoire shows us even more: a young man – an obvious lone wolf and still a family-oriented man, a man with humour and fickleness having the greatest self-confidence and the most abysmal doubts. Even in terms of how to place him nationally – highly elusive, half of the continent – how modern! – all in one single gestalt: a tall, young Italian in conspicuous clothes, whom one, for this reason, would surely call „Americano“, who speaks the language of France and lives in Flanders, while his brother builds cars in Alsace. The dachshund that accompanies him is a German? After all, he has the German name »Wurst« (sausage).

Keeping the memory alive and the magnificent rediscovery of Rembrandt Bugatti for a wide audience is, as it was often the case in the past, first the work of individuals; people who fight for their convictions over years and decades beyond all fashions, who restlessly and laboriously save works, sources and documents, trace descendants, record traditions and exhibit art. Véronique Fromanger and the people close to her have done all of this.

A monographic repertoire is the highest acclaim of a life’s work – and, within itself, the same thing: a mission of titanic proportion. Rembrandt Bugatti – and all of us – owe much to the author of the book at hand. „I hope and believe that I will succeed in creating a life’s work that no contemporary or previous animal sculptor had ever created“, wrote Bugatti. The monographic repertoire at hand proves that his hope came true. The serious and profound manner in which Rembrandt captured the wealth of the world in his sculptures make him one of the most unique artists in the history of sculpture.

Berlin, October 2014

Philipp Demandt

Director of the Alte Nationalgalerie en 2014

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

et depuis 2016 directeur des musées de Francfort , en Allemagne

English translation by Damian Kridlo

Of course, I knew the name of the sculptor which was written on the identification plate on that work displayed in Maastricht; I had seen pictures, of course, in the one or other monographic repertoires of his works. But never before did I have one of his works stumble directly upon me.

Today, I know that I was in luck to come across Rembrandt Bugatti in one of his major works, the hamadryas baboon, one of the most incredible sculptures that exists. For me, it was love at first sight.

Not too many years later – in the meantime, I had gone from the official advisor of the German Kulturstiftung der Länder (German Cultural Foundation of the Federal States) to the director of the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery) in Berlin – this love should find its utmost fulfilment, when, as to the question of the subject of my first own exhibition, there could only be one possible answer: Rembrandt Bugatti.

On the evening of 27th March 2014, we opened the first major solo exhibition of this artist at a museum, worldwide, who sank into oblivion after his early death, and, in spite of an international collector community, had nearly been completely ignored by museums. And, this Spring evening on the Museum Island in Berlin was, without a doubt, one of the happiest and one of the most fulfilling days in my professional life.

Delicate, dark stands with over 80 of Bugatti’s bronze sculptures spread through all of the halls of the Alte Nationalgalerie and appeared in such a way before the magnificent paintings on the walls – from Menzel and Manet, Liebermann and Böcklin, Courbet and Corot, Renoir and Segantini, Rembrandt’s Uncle, whose painting Berlin owns the magnum opus - returning home.

The sculptor Bugatti stood comparison to all of these great artists, for he was a man, who came from the 19th Century, advanced far into the 20th Century and finally created an oeuvre that left behind historic categories. Thus, many of his sculptures appear to us today as if they were created some 20, 30 or 40 years later – a comparison with Giacometti or Marini comes to mind. And yet, there still is the immediate curiosity of the Belle Époque, which was still unbowed up to the inferno of the Great War, after which human kind was no longer the same.

And, when looking and listening carefully, it became forthwith obvious that Bugatti’s works more than merely bore comparison with the major works surrounding his in the Alte Nationalgalerie. Rather, the language of his animals suddenly elicited, from the works of the greatest masters, answers, facets, tones, which until then had been unheard.

Didn’t one hear, when observing face to face such delicate, nearly staggering panthers, the verses of Rilke’s famous poem „The Panther“, which had only come into being shortly before then at the same zoo in which Rembrandt, as well, found his models? „His gaze going past those bars / has got so misted with tiredness, it can take in nothing more. / He feels as though a thousand bars existed, / and no more world beyond them than before. “

Didn’t one believe to smell the wet earth, out of which Bugatti‘s stupendous, early cows in the Barbizon Hall of the Alte Nationalgalerie practically rose, and didn’t one become aware of this aroma from the damp forests, meadows and gardens on the paintings of Daubigny, Rousseau and Diaz de la Pena, as well?

And didn’t Manet’s magnificent in the conservatory suddenly seem that much more heated up and nebulous in the presence of Bugatti‘s potent hamadryas baboon in the hall? Didn’t the unrelated, buttoned-up human couple in that oppulent greenhouse appear that much more unsettling in the face of the two jackals, which were affectionately sniffing each other? Wasn’t it a coincidence that this painting had caused a scandal, when, in 1896, it was acquired as the first Manet, worldwide, by a museum, Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie? And, weren’t the portraits by Anton Graff that were concentrated and celebrating pure humanity suddenly an obvious frame for Bugatti‘s no less familiar portrait of the French bulldog?

Didn’t the yawning hippopotamus, which zoologists think is rather threatening, shout, as it were, a most earthly commentary across towards Böcklin’s all too meaningful isle of the dead? And, finally, didn’t the existential paintings by Max Beckmann and Lovis Corinth on the eve of World War I seem that much more relentless in view of the exciting devouring lion by Rembrandt Bugatti?

The finale to the exhibition culminated in the famous Caspar David Friedrich Hall of the Alte Nationalgalerie, quasi the heart of the German psyche, where the paintings of the great Romanticist and Bugatti’s last creations, before his suicide, formed a symbiotic relationship, which one, upon first consideration, would have thought to be, of course, less probable, for animals did not play a role in Friedrich‘s pantheistic landscapes – with one exception: the birds – the angels of heaven and death, so to speak, the intermediaries between the worlds and spheres. Thus, Bugatti’s fateful, volumetric two vultures seemed to have escaped from Friedrich‘s giant mountains, as the only creatures, who were granted to associate between the earthly and the godly – that realm, which remains inaccessible for the human imagination, according to Friedrich’s firm conviction.

And, in front of the wall in that hall, which otherwise displays the world-famous pair of paintings – the monk by the sea and the abbey in the oakwood, Bugatti’s Christ on the cross and his five old horses constituted the last image of the exhibition. Never, in the year of the commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of the beginning of World War I, did I witness human beings standing more still and, simultaneously, more moved in front of a sculpture than before Bugatti‘s five old horses; without any doubt, one of the most impressive – and still, being entirely unmelodramatic – creations in the history of art. A visitor wrote me a letter in which she told me that tears had come into her eyes. I thought – that’s not a coincidence. Because, in the end, it wasn’t the grandiose name, the unbelievable talent or the famous family, neither the tragic story nor the Noah’s Ark of his animals, but rather the deeply perceived humanity of Rembrandt Bugatti‘s art, which connected him to Caspar David Friedrich’s incomparable landscapes and which was and still is able to touch the people at their very core.

A hundred years ago, where war and dissolution were looming on the horizon, human beings appeared barbarian to Bugatti; and animals, civilised. Rembrandt felt amongst humans like being in the „wilderness amongst savages“ towards the end of his life. „The work at the zoo, where I spend my days, is my only consolation”. His life was a meteorite of art history, curiously diffuse, without any tail and impact, which passed by and was soon forgotten. So, how does the world look 100 years later? Here, I make no reply. Just one thing: Rembrandt Bugatti’s art is as contemporary as ever.

The present monographic repertoire shows us the opulence of shapes, areas and perspectives of Rembrandt Bugatti’s art, conceived with a kind of certainty and freedom that even the greatest challenges, in view of his mooching-around models, mastered without an effort: a photographic memory, a quasi one-to-one transfer from eye to hand; not an animal sculptor, rather a born sculptor per se; an absolute talent in sculpture, a man, whom every vehicle seemed to be fitting, in order to capture life in all of its forms and feelings; a portraitist of humans and animals, for whom the fauna from every continent, in the end, opened a world of patterns and structures, rhythms and means of behaviour, which, in order to tap the fullest potential, would have brought other talent to their limits.

And, the monographic repertoire shows us even more: a young man – an obvious lone wolf and still a family-oriented man, a man with humour and fickleness having the greatest self-confidence and the most abysmal doubts. Even in terms of how to place him nationally – highly elusive, half of the continent – how modern! – all in one single gestalt: a tall, young Italian in conspicuous clothes, whom one, for this reason, would surely call „Americano“, who speaks the language of France and lives in Flanders, while his brother builds cars in Alsace. The dachshund that accompanies him is a German? After all, he has the German name »Wurst« (sausage).

Keeping the memory alive and the magnificent rediscovery of Rembrandt Bugatti for a wide audience is, as it was often the case in the past, first the work of individuals; people who fight for their convictions over years and decades beyond all fashions, who restlessly and laboriously save works, sources and documents, trace descendants, record traditions and exhibit art. Véronique Fromanger and the people close to her have done all of this.

A monographic repertoire is the highest acclaim of a life’s work – and, within itself, the same thing: a mission of titanic proportion. Rembrandt Bugatti – and all of us – owe much to the author of the book at hand. „I hope and believe that I will succeed in creating a life’s work that no contemporary or previous animal sculptor had ever created“, wrote Bugatti. The monographic repertoire at hand proves that his hope came true. The serious and profound manner in which Rembrandt captured the wealth of the world in his sculptures make him one of the most unique artists in the history of sculpture.

Berlin, October 2014

Philipp Demandt

Director of the Alte Nationalgalerie en 2014

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

English translation by Damian Kridlo

Berlin 2014 exposition rétrospective Alte Nationalgalerie

Toute une vie avec Bugatti: Alain Delon 1935-2024: en 2016 la journaliste Valérie du Figaro lui demande : "vous auriez aimé le rencontrer?" Alain Delon lui répond avec émotion en retenant son souffle: "ouf....j'aurais été son objet, son serviteur, saurait été formidable il y a tout chez Bugatti, toute la vie, tous les sentiments sont dans ses oeuvres, j'ai envie de les embrasser comme un fou" A whole life with Bugatti: Alain Delon 1935-2024: in 2016 the journalist Valérie from Le Figaro asked him: "would you have liked to meet him?" Alain Delon answered her with emotion, holding his breath: "phew....I would have been his object, his servant, it would have been great there is everything in Bugatti, all life, all feelings are in his works, I want to kiss them like crazy"

De 1979 à 2024, la collection Alain Delon. Que peut-on dire d'un homme comme lui? Dans le monde entier Alain Delon est une icône, déjà une légende, une image étincelante, charnelle, sauvage.Mais, derrière les mots et les images, il n'y a plus qu'un artiste solitaire dont la sensibilité à fleur de peau est extrême. Collectionner les oeuvres d'art fut toujours pour lui un mode d'expression vital.Sa rencontre avec Rembrandt Bugatti était inévitable. From 1979 to 2024, the Alain Delon collection. What can we say about this man? Worldwide Alain Delon is an icon, already a legend, a sparkling, carnal, wild image. But behind the words and the images there is only one solitary man, an artist whose sensitivity is extreme. Collecting works of art is for him a vital mode of expression. His meeting with Rembrandt Bugatti was inevitable.